The phrase illuminated manuscript most likely conjures images of a book with a

decidedly Western European origin. European civilization was, however, not the sole participant

in the making of illuminated manuscripts. All of the other literary centers in the world produced

illuminated manuscripts, and produced them with at least equal skill and devotion. I chose to

concern this web page the world's literary status as of the late 15th and 16th centuries, focusing mainly on

Islamic, European, and Asian manuscripts. The page will be a comparison between various manuscript producing regions and civilizations.

|

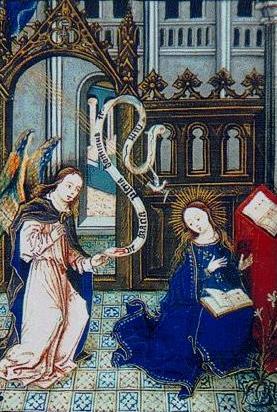

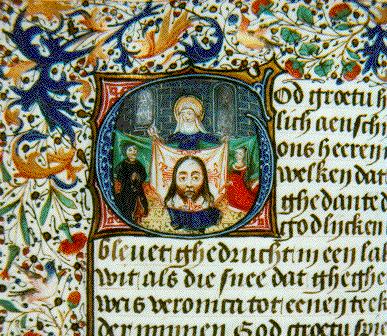

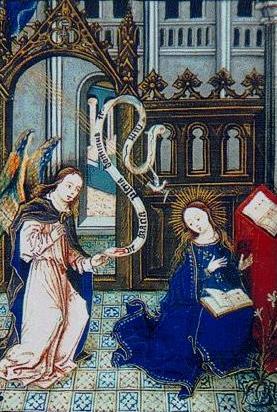

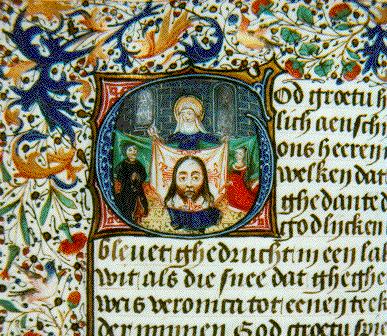

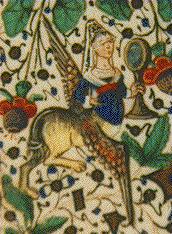

During the middle ages, the book was not used exclusively in religious context, but religion played such a dominating role at the time that a large portion of works to be dealt with concern religion. What better way, after all, to perpetuate the Word of God? With the book, religion was able to make a strong foundation in the ever- increasing world of literacy. The middle ages, however, was not a time fully severed from an oral and visual past; literacy had only begun its growth. The producers of manuscripts knew that their books would blend both literacy and visual aspects. In these manuscripts, the illustration accompanying the text functioned to assist the partially literate society in understanding of the text. In Kirby1 and similar religious works, the text signifying the main events in Mary's life is introduced with an illumination that acts as visual evidence of what is occurring in the text's story (Pacht 155). The picture to the left is an example of an illumination that reinforces ideas, those of the annunciation, by communicating visually rather than in writing. The historiated initial in the image to the right functions in the same manner. |

|

This interplay of script and art was revered commonly by all of the main book

producing centers of the time. Islamic and European scribes alike placed much spiritual

significance in the various facets of manuscript making. Aesthetic conceptions ensured that

calligraphy was molded with utmost care to embrace harmony of shape and size (Gray 32). The

making of manuscript was even held to be a form of spiritual "bonus." Christians did not merely

regard the book as an object, but as a "witness to the promise of salvation" (Pacht 33). An

illuminator of a religious text would then himself be a witness to and vessel for the

continuation of salvation. Similarly, the non-Christian literate world believed that the

processes of writing and illuminating the books was a sort of spiritual art utilizing their

hands as corporeal tools (Pacht 45). Also, the shared view that the brilliance of gold was a symbol

of transcendental light and power helped form the abundance of gold in illuminated manuscripts (Pacht 140).

The calligraphy in some Qur'ans consisted

entirely of gold! (James 10)

Illuminated

manuscripts came in many forms. Certain characteristics of these forms were essentially

global. MS of popular piety and hagiography tended to have large descriptive paintings.

Cosmological and scientific texts generally had only one or two diagrams, usually of a

schematic nature. Poetic or literary manuscripts were small with fewer illustrations than

the hagiographic manuscript (Lowry 48).

Kirby1, a book of hours,

is an example of a hagiographic

manuscript. Books of hours had hagiographic counterparts in foreign works. One religious

Indian work, the Jaina Kalpasutra, bore many similarities to the European book of hours. The

sections that the two types of books were divided into were very similar. As the book of hours devotes sections to

the important events in the Virgin Mary's life and the calendar of saints, the Kalpasutra's of the

15th and 16th centuries had a Jinacarita which illustrated the auspicious events in the lives of

important figures of Indian religion (Brown 11). As each of the Christian saints is illustrated with their own

symbols, the pictures of the Jinas(Saviours) are accompanied by illustrations of their specific

symbols (Brown 12, Thorpe 3). The function of the books for private devotions in a highly visual society kept format

ties in books from the various regions.

Similarities were not limited to books which performed the same function,

though. Many general trends can be found in the religious works of the differing regions.

Production was one of the facets of manuscripts that varied little between Islamic and European

cultures. One of the most well known production centers of European manuscripts was the

monastery. Qur'ans were produced in the

same manner, though. An overseer managed a "library" of monks that worked on a book, much

in the fashion of an assembly line; the tasks of calligraphy, painting, gold-leafing, etc. were handled separately

by different illuminators (James 10). In both societies, it was not uncommon for an

illuminator to be qualified for multiple tasks, however.

|

|

|

Decorations of the different manuscripts also held some characteristics in common. The decoration of the illuminated manuscript was the designs and images, most often in the margins, that were not related to the text matter. Early European marginalia consisted of vines and tendrils that had only geometric function - they were difficult to identify as plants (Pacht 140). As manuscript production developed, however, marginalia became more and more intricate. Eventually, decoration advanced to the level of highly intricate design with numerous miniatures, mainly animals, monsters, and various other objects, as shown by the images from Kirby 1 on the left. |

Arabic manuscripts were strongly affected by the Persian and Turkish influence that

flowed into previously Arabic regions after the Mongol invasion of Iran in the 13th

century. Purely Arabic manuscripts, those made before the invasion, often had unadorned

margins (Gray 48). The ones that had decoration obeyed a very strict design that was characteristic

of much of Arabic art; the marginalia

were primarily of a geometric nature. The design on the right is an example of an Arabic

decoration. Islamic manuscripts produced after the invasion, however, slowly began to abandon

the old Arabic styles and to adopt more Persian and Turkish techniques (Ettinghausen 167). Marginalia still had

geometric and vegetal design, but the characteristics which would rise into European

design (see images from Kirby 1 above) flourished also.

Arabic manuscripts were strongly affected by the Persian and Turkish influence that

flowed into previously Arabic regions after the Mongol invasion of Iran in the 13th

century. Purely Arabic manuscripts, those made before the invasion, often had unadorned

margins (Gray 48). The ones that had decoration obeyed a very strict design that was characteristic

of much of Arabic art; the marginalia

were primarily of a geometric nature. The design on the right is an example of an Arabic

decoration. Islamic manuscripts produced after the invasion, however, slowly began to abandon

the old Arabic styles and to adopt more Persian and Turkish techniques (Ettinghausen 167). Marginalia still had

geometric and vegetal design, but the characteristics which would rise into European

design (see images from Kirby 1 above) flourished also. | Arguably, one of the most fascinating aspects of illuminated manuscripts is their illuminations. Fortunately, the artistic content of the manuscripts from the various regions is the area where the largest dissimilarities occur. The reason for the chasm between the styles is the fact that Western art is fundamentally pictoral, naturalistic, and representational, and Arabic art is not (James 8). Hinted at in the marginalia of Arabic manuscripts, the geometric backbone of Islamic art is fully revealed in the non-decorative illuminations. Persian influence, as it affected marginal decoration, also transformed illuminations that appeared in manuscripts. Levels of naturalism rose, and the distinct character of early Arabic art began to fade (Gray 121). |

|

As seen in the picture on the bottom left (an excerpt from Kirby 1), Western art aims at

portraying life. Images of people, tools, buildings, and surroundings are lacking in the

illuminated Qur'an above it. Illumination

of the Qur'an was mainly an art of geometric ornament with vegetal patterns as secondary motifs.

Arabic patterns, like the patterns below, were of abstracts of aesthetic perfection -- Platonic

ideals of absolute beauty rather than attempts at depicting life (Ettinghausen 175).

|

Although there was a strong difference between the illuminations of pure Arabic

manuscripts and other manuscripts, the was a prevailing method of design that was common

amongst the paintings that were naturalistic and descriptive of life, i.e. non-Arabic. Most of

these illuminations were so similar that there seemed to be a template collective that the all

illuminators would draw from, only modifying the image slightly. Each region, of course,

had its own collective. Paintings in the Kalpasutra are heavily based on cliches, but minor

variations are allowed to the painter (Brown 1). An established canon of images also formed the

staple from which Persian illuminators drew ideas and slightly altered them for novelty

and invention (Lowry 47). European illumination was often created in the same manner.

|

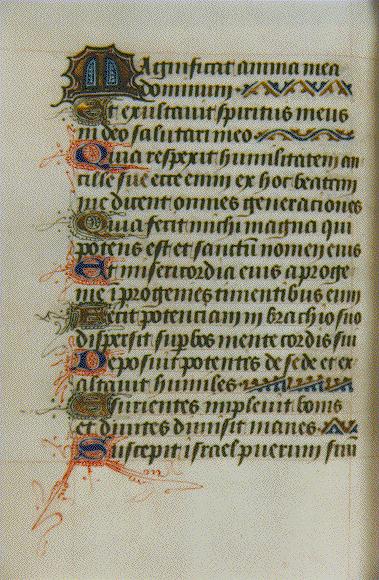

Decoration and illumination are not the only forms of creative or artistic

expression, though; every part of the illuminated manuscript was magnificent, including the text.

It is easy to see how much a role visuality played in the Middle Ages just by looking at some of

the common conventions used in the layout of Manuscript text. The aesthetic desire for a block

of text to literally be block shaped introduced many interesting methods of text spacing. In

the picture to the left, the lines in Kirby 1 which are shorter than the width of the text space

have appended to them line spacers (the gold and blue designs on the second and fourth lines of text, etc.).

Many European manuscripts employed this technique. It's interesting to notice that the spacers in Kirby 1,

an expensive wedding gift, are made of gold. Arabic and Persian illuminators didn't have the need to invent a spacing mechanism; one already existed in their alphabets. Unlike European languages that require all the letters of one word to be in proximity for the word to have any meaning, Central Asian languages had alphabets that contained special letters that didn't require the following letters of the word to be connected (An analog in the English language would be if the letter p was one of these special letters, the word "elephant" could be written as "elep hant"). This method of spacing allowed the block of text to appear well organized without artificial constructions such as line spacers (Gray 7). The image on the right shows calligraphy from an Islamic manuscript. The special characteristics of the alphabet, such as curve and spacing, allow the text conform to a prescribed fit with little effort and no extraneous devices. |

|

There is no doubt that illuminated manuscripts were important in both their

own and contemporary times. The illustration and calligraphy of manuscripts in common

places of worship touched the lives of many, and finer works embodied the elegance of

the nobility. One of the most important facets, in my opinion, to illuminated manuscripts,

however, is the fact that their presence is not limited to peoples of the past -- that they

exist in our time to be studied and treasured.